Australia’s Voice to Parliament failed - what do young people think?

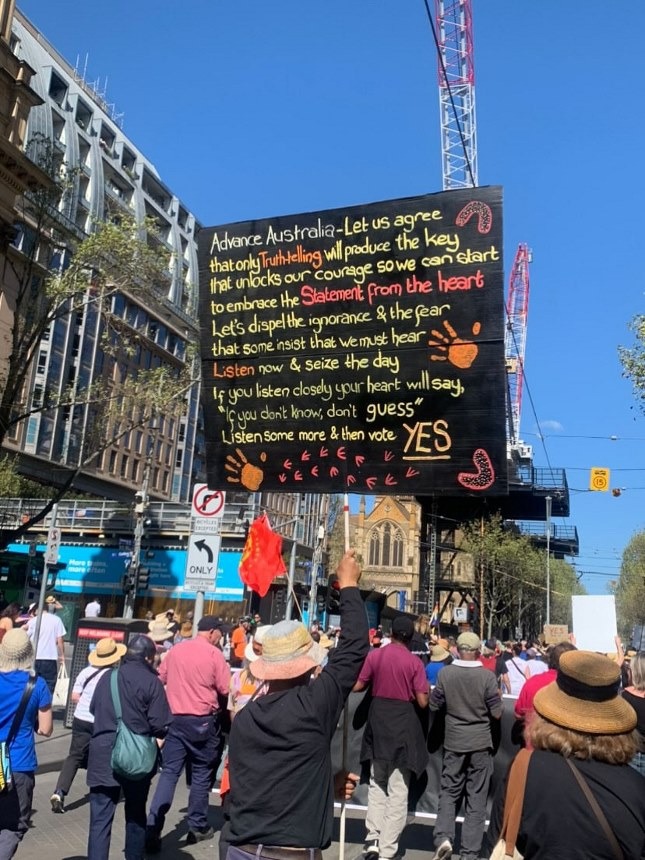

Image supplied by Sofia Jayne.

-

By Jemma van Zaanen. Originally submitted for an assignment for Newcastle University, Newcastle Upon Tyne.

“A Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. Do you approve this proposed alteration?”

This question was posed to the Australian public on October 14 and led to one of the most divisive referendums in the country’s history.

Announced by the Labor Party, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese originally pledged his dedication to the cause at the Garma Festival in 2022.

One of his election promises was to see the Uluru Statement from the Heart carried out in full - which asks for “substantive recognition in Australia’s history” for First Nations peoples.

The first step was to impose an independent advisory body made up of Indigenous peoples chosen by Indigenous peoples to advise the government on issues and matters relating to Indigenous peoples only.

The government would have been under no obligation to take the body’s advice.

But, after countless yes and no campaigns from every side of the political spectrum, Australia ultimately voted no.

Around 17 million Australians voted internationally and at the polls, and staggeringly 60.1 per cent voted no and 39.9 per cent voted yes, according to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s poll data.

Out of six states and territories, only the Australian Capital Territory wanted to see the Voice be enshrined in the constitution.

The rejection of such a media-heavy referendum is historic in Australia and has changed the country’s relationship with First Nations peoples. But why is something so monumental in Australia barely making headlines worldwide?

Danelle van Vliet, a 20-year-old Melburnian exchange student at Newcastle University, thinks people abroad are just not made aware of Australian issues.

“I didn’t think that people would know that much about it here in the UK. I thought there wouldn’t be that much discussion around it,” van Vliet said.

“I couldn’t connect to some people like I would have back home but I was still able to talk to some people about how I was feeling about the outcome.”

This sentiment is echoed by Jess Hinds, a 19-year-old English Newcastle University student. She feels she’s only aware of her own country’s news.

“When I watch the news or scroll through my newsfeed, most of the stories are only about the United Kingdom,” Hinds said.

“I barely knew about the Indigenous population in Australia, let alone a countrywide referendum. It would be good if we learnt more in school about international issues.”

With such a huge loss helmed by the popular Albanese government, many may question what led to Australia’s decision.

Media coverage and political campaigns aimed to heavily influence people’s perception of what the Voice would mean for Australian politics.

While some First Nations peoples voted no, many of the no campaigns were steeped in racism and disinformation.

One of the leaders of the no-campaign was One Nation’s leader Pauline Hanson, who also represents Queensland in Parliament. Queensland had the lowest yes vote in the country, at 31.8 per cent.

Hanson compared the Voice proposal to South Africa’s apartheid, stating it may lead to racial segregation.

But others voted no for different reasons. Young Wurundjeri activist Jasper Cohen-Hunter explains he voted no as he sees the voice as a continuation of colonisation.

Cohen-Hunter campaigned for the no vote with the Black Sovereign Union where they aimed to educate the population on Australia’s history.

“The Australian system cannot be trusted. Our community have known about constitutional recognition for 20 years but the general public wasn’t aware, the Voice is not new,” Cohen-Hunter said.

“The Voice was a public awareness campaign on what has been going on for the last 20 years. We can’t put the framework of white politics on black people.”

The fight to close the gap between First Nations peoples and Australia continues, despite the referendum not succeeding.

Post a comment